Go Programming - OOP

Concepts of Programming Languages

Sebastian Macke

Rosenheim Technical University

Sebastian Macke

Rosenheim Technical University

Go doesn't have try-catch exception based error handling.

Go distinguishes between recoverable and unrecoverable errors:

Recoverable: e. g. file not found

err := ioutil.WriteFile(src.Name(), []byte("hello"), 0644)

if err != nil {

log.Error(err)

}Unrecoverable: array access outside its boundaries, out of memory

5The "defer" statement lets us ensure that code runs before a function exits

f, err := os.Open("myfile.txt")

if err != nil {

return err

}

defer f.Close() // Will be executed on function exit, even in case of an unrecoverable error.

....

// read, writefunc getElement(array []int, index int) int { if index >= len(array) { panic("Out of bounds") } return array[index] } func getElementWithRecover(array []int, index int) (value int) { defer func() { r := recover() if r != nil { fmt.Println("Recovered with message '", r, "'") } value = -1 }() return getElement(array, index) } func main() { array := []int{3, 4, 5} ret := getElementWithRecover(array, 3) fmt.Println("return value: ", ret) }

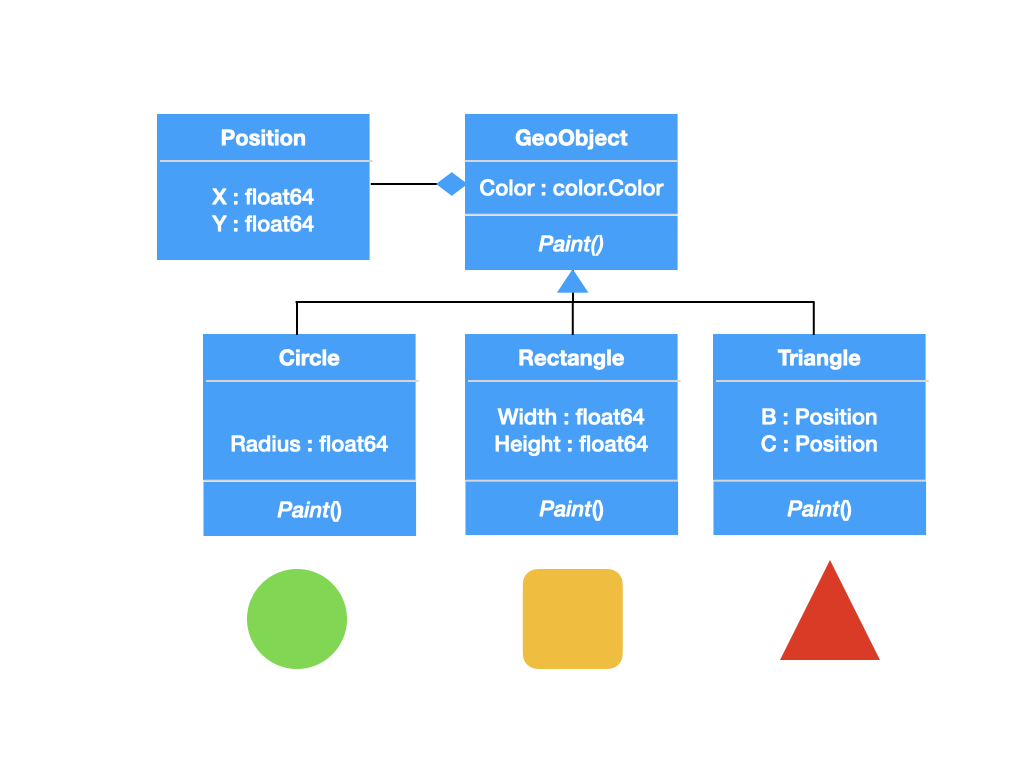

Wikipedia: Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm based on the concept of "objects", which can contain data and code: data in the form of fields (often known as attributes or properties), and code, in the form of procedures (often known as methods).

Go is not a pure object oriented programming language but

allows an object-oriented style of programming

// Rational represents a rational number numerator/denominator. type Rational struct { numerator int denominator int } // Constructor func NewRational(numerator int, denominator int) Rational { if denominator == 0 { panic("division by zero") } return Rational{ numerator: numerator, denominator: denominator, } }

// Multiply method for rational numbers

func Multiply(r Rational, y Rational) Rational {

return NewRational(r.numerator*y.numerator, r.denominator*y.denominator)

}// Multiply method for rational numbers

func (r *Rational) Multiply(y Rational) Rational {

return NewRational(r.numerator*y.numerator, r.denominator*y.denominator)

}

r1 := NewRational(1, 2)

r2 := NewRational(2, 4)

r3 := r1.Multiply(r2)The variable r is in both cases similar to the Java this, which reference to the class instance

13package main import "fmt" type MyInt int func (b *MyInt) Inc() { *b = *b + 1 } func main() { var b MyInt = 10 fmt.Println(b) b.Inc() fmt.Println(b) }

package main import "fmt" type Bar struct{} func (b *Bar) GetHello() string { fmt.Println(b) return "Hello" } type Foo struct { B *Bar } func main() { var f Foo fmt.Println(f.B) // Output "nil" fmt.Println(f.B.GetHello()) // Null Pointer error or "Hello"? }

Encapsulation of methods is basically is just a syntax element.

func (r *Rational) Multiply(y Rational) Rational {

....

}is internally transformed into

func Multiply(r *Rational, y Rational) Rational {

....

}A lot of languages do it this way.

16Composition and inheritance are two ways to achieve code reuse and design modular systems

class Engine {

....

}

class Car {

private Engine engine

}class Animal {

....

}

class Dog extends Animal {

}Composition and inheritance are two ways to achieve code reuse and design modular systems

www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ng8m5VXsn8Q&t=414s

class Runner {

public void run(Task task) { task.run(); }

public void runAll(List<Task> tasks) { for (Task task : tasks) { run(task); } }

}

class RunCounter extends Runner {

private int count = 0;

@override public void run(Task task) {

count++;

super.run(task);

}

@override public void runAll(List<Task> tasks) {

count += tasks.size();

super.runAll(tasks);

}

}When I run 3 tasks with RunCounter.runAll, what value does count have?

19// Point is a two dimensional point in a cartesian coordinate system. type Point struct{ x, y int }

// ColorPoint extends Point by adding a color field. type ColorPoint struct { Point // Embedding simulates inheritance but it is (sort-of) delegation! c int }

fmt.Println(cp.x) // access inherited field

// Point is a two dimensional point in a cartesian coordinate system.

type Point struct{ x, y int }

// ColorPoint extends Point by adding a color field.

type ColorPoint struct {

Point // Embedding simulates inheritance but it is (sort-of) delegation!

c int

}

var Point p = Point{}

var ColorPoint cp = ColorPoint{}

p = cp // Compile Error

p = cp.Point // WorksAn interface is a set of methods

In Java:

interface Switch {

void open();

void close();

}In Go:

type OpenCloser interface {

Open()

Close()

}class Door implements Switch {

public void Open() { ... }

public void Close() { ... }

}type Door struct {}

func (d *Door) Open() { ... }

func (d *Door) Close() { ... }Door implicitly satisfies the interface OpenCloser

Go supports polymorphism only via interfaces

25The print functions in the fmt package support the following interface

type Stringer interface {

String() string

}if tmp, ok := object.(Stringer); ok {

// The object implements stringer

}package main import "fmt" type DoorOpen bool func (d DoorOpen) String() string { if d == true { return "Door is open" } else { return "Door is closed" } } func main() { var d DoorOpen = false fmt.Println(d) }

An implementation can support multiple interfaces at the same time.

27func main() { var p = Point{1, 2} var cp = ColorPoint{p, 3} // embeds Point fmt.Println(p) fmt.Println(cp) fmt.Println(cp.x) // access inherited field // s is an interface and supports Polymorphism var s fmt.Stringer s = p // check at compile time fmt.Println(s) s = cp fmt.Println(s) }

func main() { var someValue any someValue = 2 PrintVariableDetails(someValue) someValue = "abcd" PrintVariableDetails(someValue) if tmp, ok := someValue.(string); ok { fmt.Println("someValue is a string and has the value", tmp) } }

type any = interface{}* The error interface

func divide(a, b int) (int, error) { if b == 0 { return 0, errors.New("division by zero") } return a / b, nil } func main() { // Successful division result, err := divide(10, 0) if err != nil { fmt.Println("Error:", err) } else { fmt.Println("Result:", result) } }

The error is just an interface with one method that should return the error message:

type error interface {

Error() string

}

github.com/s-macke/concepts-of-programming-languages/blob/master/docs/exercises/Exercise3.md

32type Foo struct { Name string } type Bar struct { Name string } type X struct { Foo Bar } func main() { y := X{ Foo: Foo{Name: "Foo!"}, Bar: Bar{Name: "Bar!"}, } fmt.Print(y.Foo.Name) fmt.Print(y.Bar.Name) //fmt.Print(y.Name) // compile error, Ambiguous Reference }