Forth

Concepts of Programming Languages

Sebastian Macke

Rosenheim Technical University

Last lecture

- Exception Handling. Error return codes vs. Exceptions

- Dynamic Types in Go

- Object Oriented Programming Principles

- Object Oriented Programming without class hierarchy

- Reasons from Go team: Inheritance can cause weak encapsulation (override) , tight coupling (difficult to refactor) and surprising bugs

- Delegation

- Implicit satisfied interfaces

2

Some thoughts about this lecture

- In history there has been developments in language design which had a significant influence

- They had unique ideas from which we can learn from

- These languages are used only a niche language today

- Forth is one of these candidates

- While Forth might be a niche language, its concepts are wildly used in other contexts

- It is so easy, that it is used in embedded systems or because of its zero dependencies can even work as a stand alone operating system

3

Prefix notation, Infix notation, and Postfix notation

- The way to write arithmetic expression is known as a notation.

- Arithmetic expressions can be written in three different. but equivalent notations:

Infix Notation

Prefix Notation

Postfix Notation

These notations are named as how they use operator in expressions.

4

Infix Notation

- We write expression in a way that the operators are placed between operands, e. g.

- Infix notation is the most common notation in the world.

- It is easy for us humans to understand, but it is hard for computers to understand. An algorithm to process info infix nitation could be difficult and costly in terms of time and space consumption

- The order of operations is important

- Parantheses are neccecary to group expressions

- Evaluate 2 + 3 * 5

+ First: ( 2 + 3 ) * 5 = 5 * 5 = 25

* First: 2 + ( 3 * 5 ) = 2 + 15 = 17

Prefix Notation

- Operators are pre -fixed by operands, i. e. operator is written ahead of operands

- + a b This is equivalent to its infix notation a + b

- Prefix notation is also known as Polish notation

+ 2 * 3 5 = + 2 15 = 17

* + 2 3 5 = * 5 5 = 25

- No parenthesis are needed

- That's how the programming languages Lisp and Scheme work

6

Postfix Notation

- Known as reversed polish notation

- The operator is *post*fixed to the operands

- The operations are written after the operands

- a b + is equivalent to its infix notation a + b

2 3 5 * + = 2 15 + = 17

2 3 + 5 * = 5 5 * = 25

- No parenthesis are needed here either

7

Examples

a * b + c =>

c * (a + b) =>

(3 * a - b) / 4 + c =>

(0.5 * a * b) / 100 =>

(n + 1) / n =>

x * (7 * x + 5) =>

Examples

a * b + c => a b * c +

c * (a + b) => c a b + *

(3 * a - b) / 4 + c => 3 a * b - 4 / c +

(0.5 * a * b) / 100 => 0.5 a b * * 100 /

(n + 1) / n => n 1 + n /

x * (7 * x + 5) => x 7 x * 5 + *

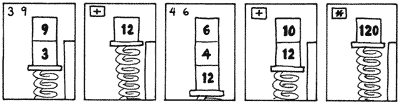

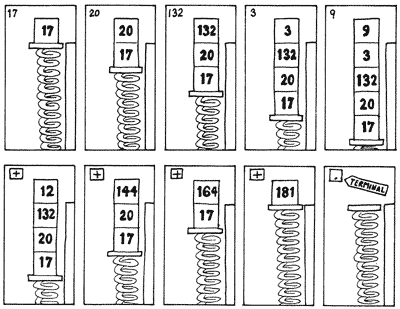

Postfix via a stack machine

Evaluate

3 push 3 onto stack

9 push 9 onto stack

+ pop 3 and 9 from stack, add them, push result onto stack

4 push 4 onto stack

6 push 6 onto stack

+ pop 4 and 6 from stack, add them, push result onto stack

* pop 12 and 15 from stack, multiply them, push result onto stackPostfix via a stack machine

Evaluate

11

Stack machines are rather simple to implement

func main() {

var s stack

fields := strings.Fields("2 3 5 * +")

for _, expr := range fields {

fmt.Println("Parse ", expr)

switch expr {

case "+":

s.Push(s.Pop() + s.Pop())

case "*":

s.Push(s.Pop() * s.Pop())

default:

v, err := strconv.Atoi(expr)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println("Unknown expr", expr)

return

}

s.Push(v)

}

}

println("result:", s.Pop())

}

12

Forth - Easier than Assembler

13

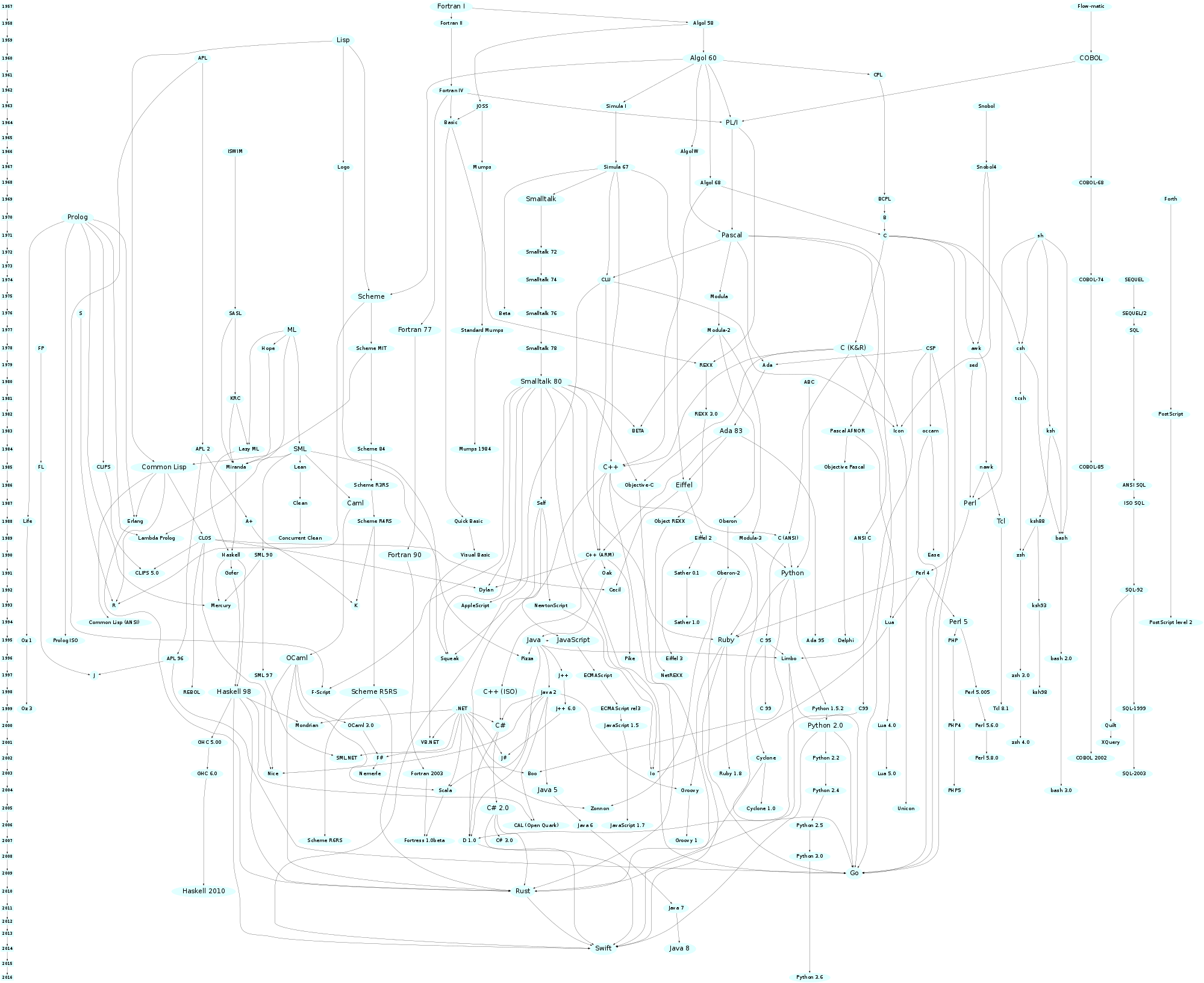

History

- Invented by Charles H. "Chuck" Moore in 1968

- Used mainly in the early microcomputers. Implementations for almost all computer types.

- Standardized ANSI Forth in 1994

img/01-languages.png

14

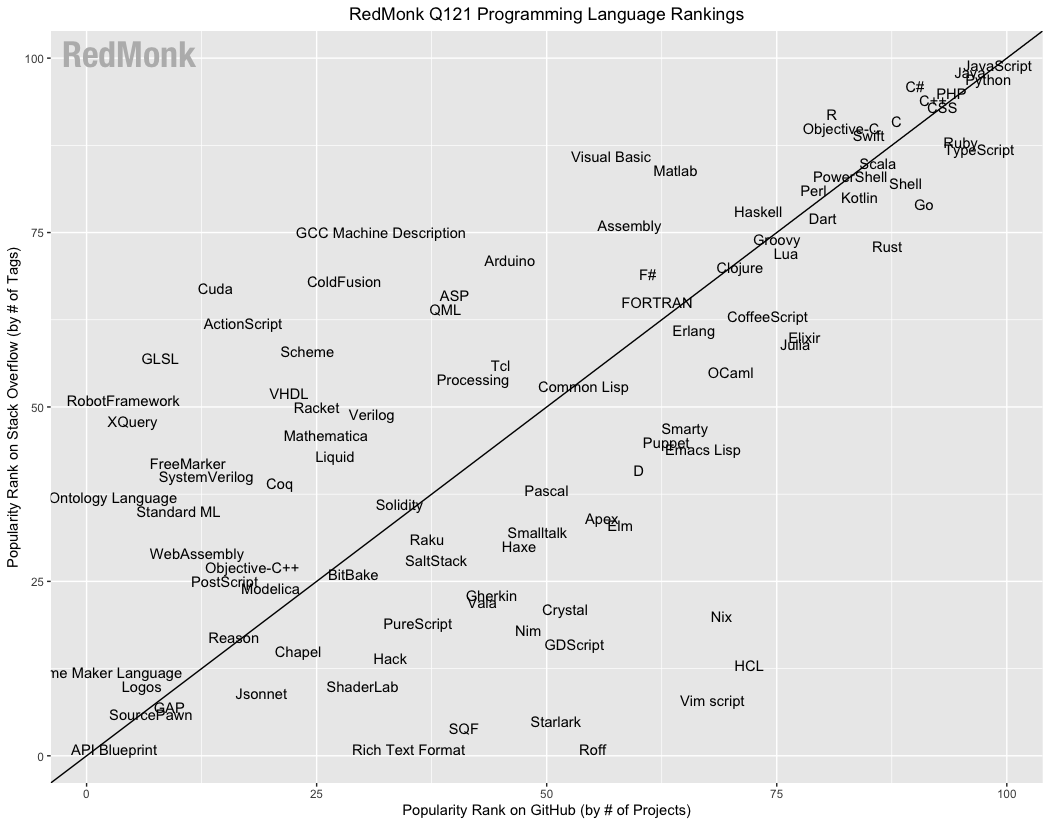

Forth doesn't show up in this benchmark

15

Features

- The most minimalist language regarding syntax you can imagine

- Stack machine with reverse polish notation

- No types, just integers

- No character limits to define names such as variable names or function names.

- No (fixed) keywords

- Procedural language

- Control structures, loops, and conditionals

- Reflection

- Direct access to call stack (return stack)

- Able to invent new language features on the fly

16

Features

- Forth is a compiled and interpreted language at the same time

- Debugging capabilities during runtime because of built in interpreter

- Compiles to threaded code (something in between bytecode and compiled code). Contains an implicit compression

- Entire development environment—including compiler, editor fits in a few kiloByte of machine language

- Probably the most ported language ever

17

Websites to experiment with Forth

s-macke.github.io/Forthly/

www.tutorialspoint.com/execute_forth_online.php

www.jdoodle.com/execute-forth-online/

Online tutorial

www.forth.com/starting-forth/0-starting-forth/

learnxinyminutes.com/docs/forth/

18

Components of the Language

- Stack: Stores intermediate results as integers

- Return Stack: Stores the function call return addresses. Directly accessible.

- Dictionary: Stores all command words and their definitions

- Interpreter: Interpretively executes commands found in the dictionary using the stack to store calculations

." Hello World!" cr - prints "Hello World" and a newline (carriage return)

. - pops the top of the stack and prints its value

.s - shows the content of the stack

words - shows all the available words in the dictionary

e. g.

- '+' '*' '.', '.s' 'words' '."' are called words

- The interpreter only differs between words and numbers. It the word is not found in the dictionary, it is interpreted as a number, which is pushed onto the stack

19

Stack operations

As a stack machine, there are a few operations that on manipulating the stack.

- dup - Duplicated the top of the stack

- swap - swaps the top 2 elements

- drop - drops the top element of the stack

- rot - rotate the top 3 numbers

- 2dup - duplicates the top 2 elements

20

Constants

The constant <name> word adds a new word into the dictionary which pushes the constant value of <name> onto the stack.

42 constant fourtytwo

fourtytwo . ( outputs 42 )

What is the output of the following code?

Comments

"(" and ")" are words in the dictionary. They are used to mark the beginning and end of a comment. The word "(" searches for the next ")" word and jumps to it.

21

Store and fetch variables

- The variable <name> word allocates storage for an integer in the dictionary. (There is no difference between the heap and the dictionary)

- Adds a new word into the dictionary which pushes the address of the variable on the stack

- @ - fetches the value of the variable from the given pointer on the stack

- ! - stores the top of the stack into the variable

variable x ( equivalent to var x int )

1 x ! ( equivalent to x = 1 )

x @ . ( equivalent to print(x) )

x @ 1 + x ! ( equivalent to x = x + 1 )

Functions: Adding a word

: square dup * ;

2 square . ( outputs 4 )

2 is placed on the stack, duped, then the result is multiplied by itself.

23

Conditionals

- In Forth, true has the numeric value of -1 and false has the value of 0.

- a 32-bit binary with the value -1 is in binary 11111111111111111111111111111111b

- Conditional operators pops the top 2 values on the stack and push the boolean onto the stack

false invert . ( outputs true )

1 2 < . ( outputs true )

1 2 = . ( outputs false )

1 2 and . ( outputs true )

other words: <, >, =, <>, <=, >=, 0=, and, or, xor

24

Control Structures

- if else then

- do loop

- begin until

25

If then else

- if tests the top of the stack

- if true, then executes code from if to else

- if false, then code from else to then is executed

Absolute value:

: absolute ( returns the absolute value )

dup 0 < if -1 * then ;

-100 absolute . ( outputs 100 )

Boolean output:

: .bool ( prints the boolean )

-1 = if ." true" else ." false" then ;

false .bool

do loop

- 2 parameters need to be pushed:

- limit - number of times to execute the loop

- index - the starting index for the loop

do loop copies these two values onto the call stack

- i is a special word that pushes the value of index from the return stack back to the main stack

- j is like i and is used for nested do loops

- leave or unloop breaks out of a do loop

: countdown ( count down from ten to zero )

11 0 do

10 i - .

loop ;

countdownbegin until

begin <body> <condition> until

- Similar to a do while loop

begin <condition> while <body> repeat

: countdown

0

begin

dup 10 swap - . cr

1 +

dup 10 = until ;

countdownstrings

- Stores the <string> in the heap and pushes the address of the string and its length onto the stack

: printEachChar

0 do ( the length of the string is already on the stack )

dup i +

c@ emit cr

loop

;

s" This is a string"

2dup type ( outputs the string )

printEachChar ( outputs each character )

- c@ loads only one byte from the given address

- emit prints the given integer as ASCII

29

Exercise

- Write a function, which takes one integer as argument and calculates the cube x³ of that number

- Write a function which which prints the numbers from 1 to 10

- Write a function, which checks whether the given number on the stack is a prime number (loop over all odd numbers and test via the word "mod")

- Write a function "swapv", which swaps the content of two variables

variable a 1 a ! ( a = 1 )

variable b 2 b ! ( b = 2 )

a b swapv

a @ . ( outputs 2 )

b @ . ( outputs 1 )

Arrays

array with initialization

create [myarray] 10 , 20 , 30 ,

[myarray] @ . ( outputs 10 )

[myarray] cell+ @ . ( outputs 20 )

[myarray] cell+ cell + @ . ( outputs 30 )

[myarray] 2 cells + @ . ( outputs 30 )

alloc 12 bytes

create [myarray] 12 allot

[myarray] 4 + c@ ( access byte number 4 )

Extending Forth

Forth has a lot of built-in words. But most of them are just made of other words.

- The words ":", "variable", "constant" use all the next word as a name and use "create" to allocate a new word

: variable create 0 , ;

: constant create , DOES> @ ;

- Forth is so flexible that you can extend the compiler and e. g. implement structs, special loops, exceptions, etc. in your own way.

- Most words are implemented with other words. How far you can go can be easily seen by looking at the source code of

github.com/nineties/planckforth

Only 215 lines of C code and 2800 lines of bootstrap Forth code.

32

Summary

- Forth is not very readable but you can write clean code in Forth by using the open naming scheme wisely.

- The base language is simple, but the base dictionary is global and can go rapidly out of control

- the only parameter passing mechanism is the stack and is difficult to decipher. Forth encourage you to use the stack, but does not encourage you to use variables

- Once you are familiar with RPN it is a natural way to do calculations

- Weak point is the pointer arithmetic and no type checking. You can shoot yourself in the foot very easily

33

Java bytecode is actually a stack machine

public int Add(int a, int b, int c) {

return a + b + c;

}

compiles into

public int Add(int, int, int);

Code:

0: iload_1 // push parameter 1 onto the stack

1: iload_2 // push parameter 2 onto the stack

2: iadd // pop the two parameters, add them, and push the result

3: iload_3 // push parameter 3 onto the stack

4: iadd // pop the two parameters, add them, and push the result

5: ireturn // return the resultExercise: Write a calculator

35

Lexer and Parser and Interpreter

Lexer

- Reads input

- Identifies and generates a sequence of tokens (Lexing)

- Removes comments

Parser

- Performs syntax analysis

- Performs semantic validation

- Create abstract representation of the code

Interpreter

- Executes the computer program

36

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

Infix: ( ( ( A + B ) * C ) - ( ( D + E ) / F ) )

Postfix: A B + C * D E + F / -

Operand order does not change!

Operators are in order of evaluation!

Algorithm:

- Initialize a stack for operators and output list

- Split the input string into a list of tokens

- For each token in the token list:

- If the token is a number, push it onto the output list

- If the token is an operator:

- Pop operators from the stack and push them onto the output list until you find an operator

with lower precedence

- Push the current operator onto the stackShunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

1 + 2 * 3 + 4

↑

stack: <empty>

output: []

- Push "1" onto the output list

38

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

+ 2 * 3 + 4

↑

stack: <empty>

output: [1]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

2 * 3 + 4

↑

stack: [+]

output: [1]

- Push "2" onto the output list

40

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

* 3 + 4

↑

stack: [+]

output: [1 2]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

3 + 4

↑

stack: [+ *]

output: [1 2]

- Push "3" onto the output list

42

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

+ 4

↑

stack: [+ *]

output: [1 2 3]

- The operator on the top of the stack has a higher precedence than the current operator, so pop the top of the stack and push it onto the output list

- Push "+" onto the stack

43

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

4

↑

stack: [+]

output: [1 2 3 * +]

- Push "4" onto the output list

44

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

stack: [+]

output: [1 2 3 * + 4]

- Push the rest on the stack onto the output list

45

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

stack: []

output: [1 2 3 * + 4 +]

- No more elements on the stack. Finished

46

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

( ( ( A + B ) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: <empty>

output: []

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

( ( A + B ) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: (

output: []

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

( A + B ) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( (

output: []

- Push "(" onto the output list

49

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

A + B ) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( (

output: []

- Push "A" onto the output list

50

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

+ B ) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( (

output: [A]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

B ) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( ( +

output: [A]

- Push "B" onto the output list

52

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

) * ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( ( +

output: [A B]

- Pop everything from the stack and push it onto the output list until you find "("

53

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

* ( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( (

output: [A B +]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

( C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( *

output: [A B +]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

C - E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( * (

output: [A B +]

- Push "C" onto the output list

56

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

- E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( * (

output: [A B + C]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

E ) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( * ( -

output: [A B + C]

- Push "E" onto the output list

58

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

) ) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( * ( -

output: [A B + C E]

- Pop everything from the stack and push it onto the output list until you find "("

59

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

) / ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( ( *

output: [A B + C E -]

- Pop everything from the stack and push it onto the output list until you find "("

60

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

/ ( F + G ) )

↑

stack: (

output: [A B + C E - *]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

( F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( /

output: [A B + C E - *]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

F + G ) )

↑

stack: ( / (

output: [A B + C E - *]

- Push "F" onto the output list

63

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

+ G ) )

↑

stack: ( / (

output: [A B + C E - * F]

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

G ) )

↑

stack: ( / ( +

output: [A B + C E - * F]

- Push "G" onto the output list

65

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

) )

↑

stack: ( / ( +

output: [A B + C E - * F G]

- Pop everything from the stack and push it onto the output list until you find "("

66

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

)

↑

stack: ( /

output: [A B + C E - * F G +]

- Pop everything from the stack and push it onto the output list until you find "("

67

Shunting Yard algorithm - Conversion from Infix to Postfix

↑

stack: <empty>

output: [A B + C E - * F G + /]

Exercise

github.com/s-macke/concepts-of-programming-languages/blob/master/docs/exercises/Exercise4.md

69

Last lecture

- Prefix, Infix and Post-Notation

- Stack machine

- Forth as one of the most simplistic languages

- Metaprogramming, program new language features while programming

- Shunting-Yard Algorithm

70

Thank you

Use the left and right arrow keys or click the left and right

edges of the page to navigate between slides.

(Press 'H' or navigate to hide this message.)