Concurrent Programming with Go

Concepts of Programming Languages

Sebastian Macke

Rosenheim Technical University

Sebastian Macke

Rosenheim Technical University

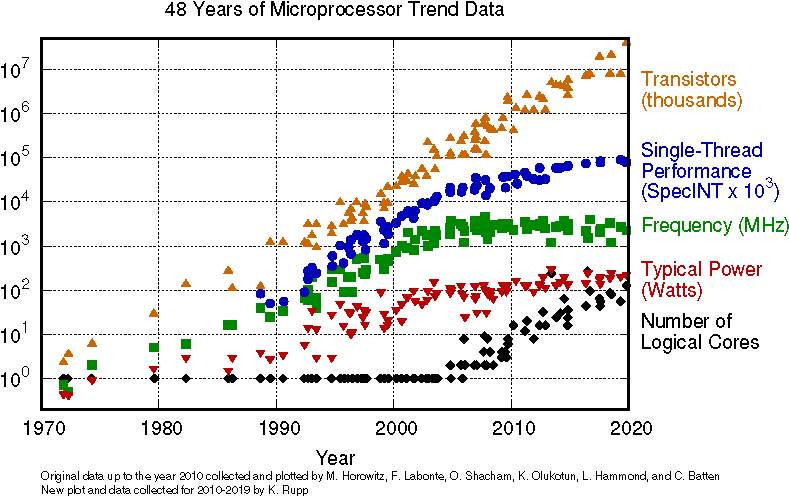

Shared memory systems are the most common types of multiprocessor computer system

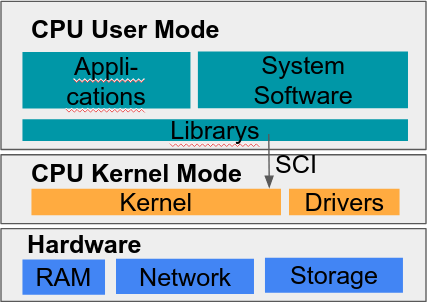

Kernel Mode: Highest Privilege level

Access to hardware via drivers, Control over RAM, File system, Memory

Kernel controls CPUs via a scheduler and provides threads to user space

User Mode: Lowest Privilege level

No direct hardware access, Calls the kernel via the System Call Interface (SCI)

All IO has to run through the kernel. E. g. A process cannot "wait" itself (Endless loop excluded).

A process can ask the kernel for threads

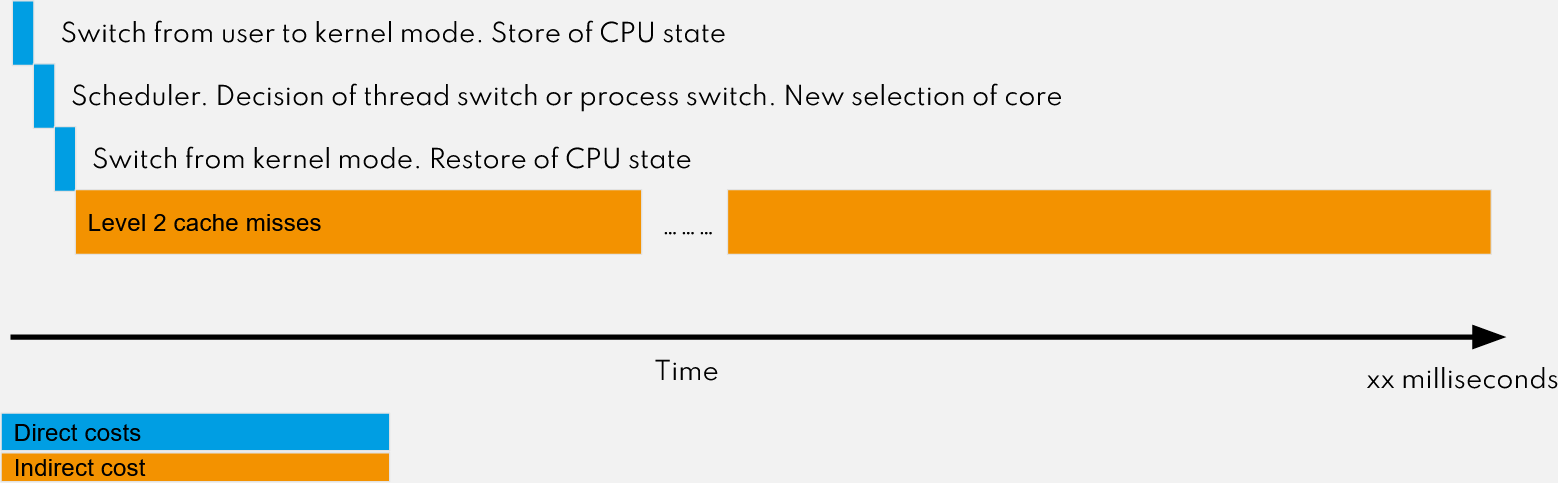

Example: Process switch for one CPU core

A task switch can take many µs up to 1ms. You should prevent context switches as much as possible.

8ExecutorService executorService = Executors.newFixedThreadPool(10); Future<String> future = executorService.submit(() -> "Hello World"); // some operations String result = future.get();

One interesting technique in this context are Coroutines.

10JavaScript example

function* test() {

var x = yield 'Hello!';

var y = yield 'First I got: ' + x;

return 'Then I got: ' + y

}

var tester = test()

console.log(tester.next()) // Output: Hello

// .. do something else

console.log(tester.next("cat")); // Output: First I got: cat

// .. do something else

console.log(tester.next("dog")); // Output: then I got: dogWhen "yield" is executed the JavaScript engine has to store the state of the function. Usually the program counter, call stack and CPU registers.

11JavaScript is single threaded. However doesn't allow to block on blocking calls.

fetch('http://example.com/movies.json')

.then(response => response.status()) // is executed as callbackasync function Download() {

var response = await fetch('https://playcode.io/')

console.log(response.status)

}

await Download()

The technique of Coroutines is implicitly used for blocking calls.

Advantage: 1. No callback hell. 2. You just don't have to worry about blocking. Just write your code down.

But: This must be a language feature directly supported by their runtime

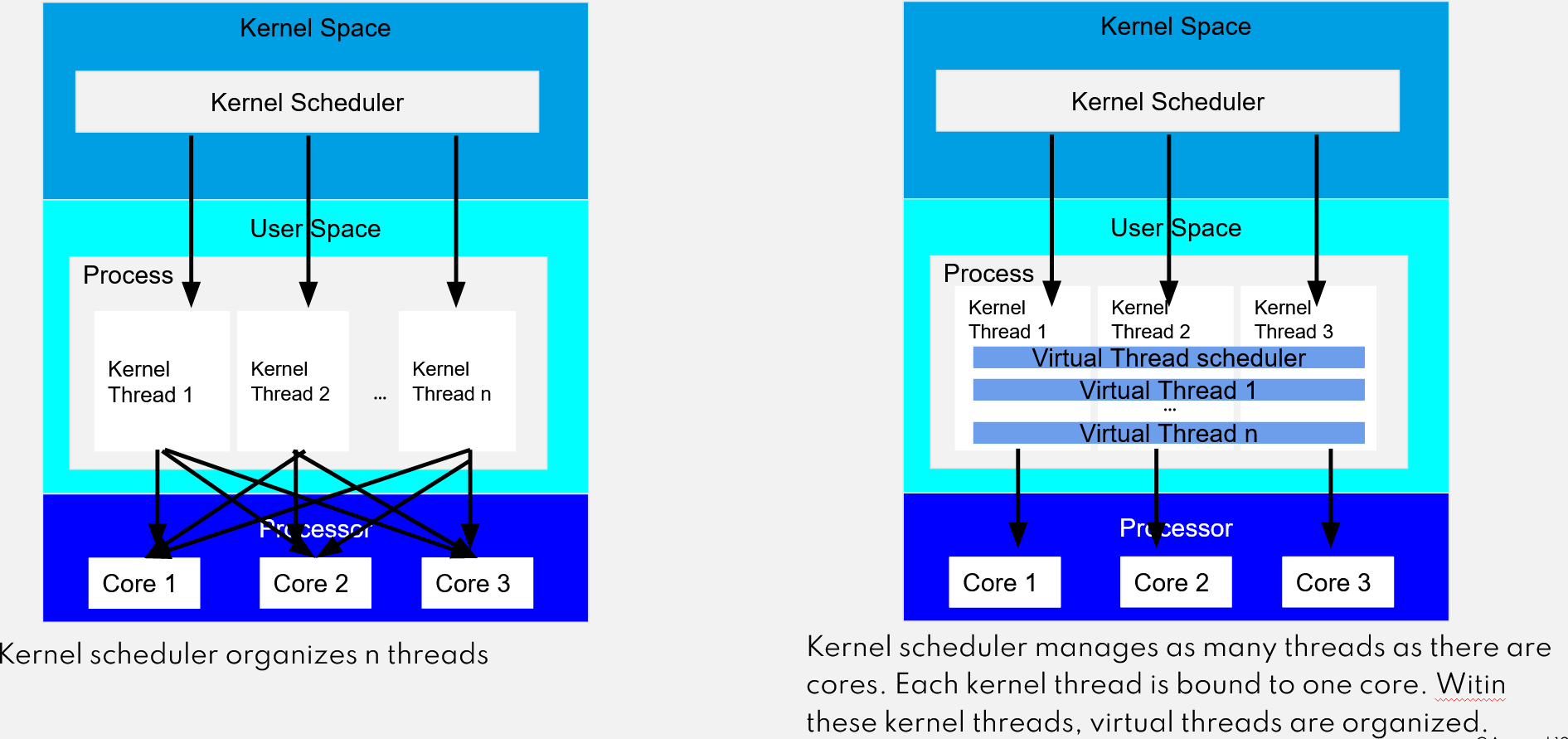

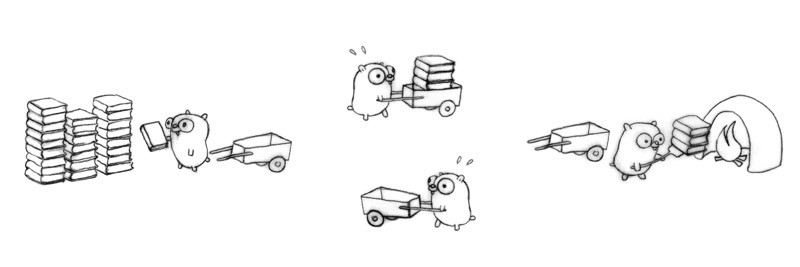

Goroutines are neither hardware nor software threads

In case of independent threads and blocking calls you can just write your code down like it is single threaded!

14A goroutine is a function running independently in the same address space as other goroutines

f("hello", "world") // f runs; we wait

go f("hello", "world") // f starts running g() // does not wait for f to return

Like launching a function with shell's & notation.

func Sleep() { time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1000)) * time.Millisecond) } func main() { fmt.Println("Number of Goroutines running: ", runtime.NumGoroutine()) for i := 0; i < 1000000; i++ { go Sleep() } for i := 0; i < 15; i++ { fmt.Println("Number of Goroutines running: ", runtime.NumGoroutine()) time.Sleep(100 * time.Millisecond) } }

var myYoutubevideo struct { likes int32 } func Viewer() { time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(300)) * time.Millisecond) myYoutubevideo.likes = myYoutubevideo.likes + 1 } func main() { for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ { go Viewer() } time.Sleep(3000 * time.Millisecond) // wait a long time fmt.Println(myYoutubevideo.likes, "likes") }

What will be the result?

18var myYoutubevideo struct { likes int32 mu sync.Mutex } func Viewer() { time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(500)) * time.Millisecond) myYoutubevideo.mu.Lock() defer myYoutubevideo.mu.Unlock() myYoutubevideo.likes = myYoutubevideo.likes + 1 } func main() { for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ { go Viewer() } for i := 0; i < 8; i++ { fmt.Println(myYoutubevideo.likes, "likes") time.Sleep(200 * time.Millisecond) } }

var myYoutubevideo struct { likes int32 } func Viewer() { time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(500)) * time.Millisecond) atomic.AddInt32(&myYoutubevideo.likes, 1) } func main() { for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ { go Viewer() } for i := 0; i < 8; i++ { fmt.Println(myYoutubevideo.likes, "likes") time.Sleep(200 * time.Millisecond) } }

var wg sync.WaitGroup func ParallelFor(n int, f func(int)) { wg.Add(n) for i := 0; i < n; i++ { go f(i) } wg.Wait() } func ProbablyPrime(value int) { if big.NewInt(int64(value)).ProbablyPrime(0) == true { fmt.Printf("%d is probably prime\n", value) } wg.Done() } func main() { fmt.Println("Start Program") ParallelFor(1000, ProbablyPrime) fmt.Println("Stop Program") }

func ParallelFor(n int, f func(int)) { var wg sync.WaitGroup wg.Add(n) for i := 0; i < n; i++ { go func(i int) { defer wg.Done() // is always called before the goroutine exits f(i) }(i) } wg.Wait() } func ProbablyPrime(value int) { if big.NewInt(int64(value)).ProbablyPrime(0) == true { fmt.Printf("%d is probably prime\n", value) } } func main() { fmt.Println("Start Program") ParallelFor(1000, ProbablyPrime) fmt.Println("Stop Program") }

This is the previous code for atomic counting.

var myYoutubevideo struct { likes int32 } func Viewer() { time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(500)) * time.Millisecond) atomic.AddInt32(&myYoutubevideo.likes, 1) } func main() { for i := 0; i < 10000; i++ { go Viewer() } for i := 0; i < 8; i++ { fmt.Println(myYoutubevideo.likes, "likes") time.Sleep(200 * time.Millisecond) } }

Use a waitgroup to wait for all threads to finish before printing the final result.

23

Constraints can improve the expression of intent and tighten the type system

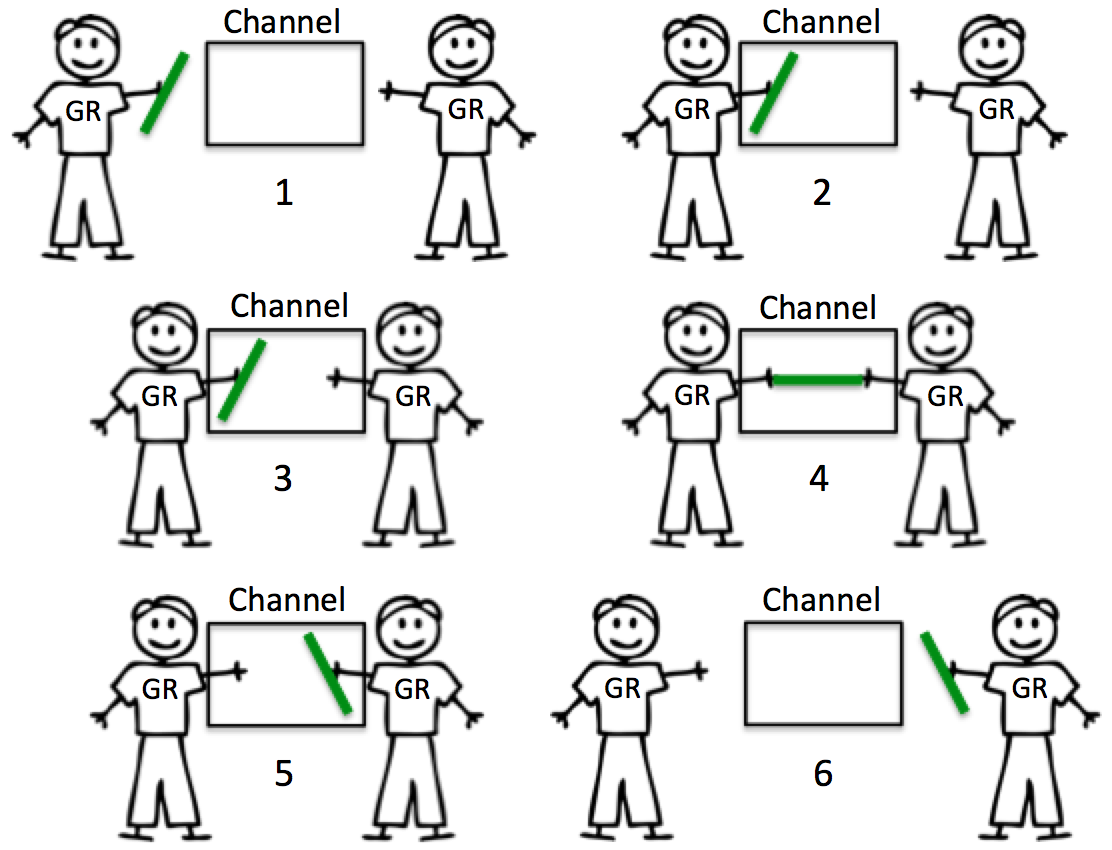

chan // read-write <-chan // read only chan<- // write only

E. g. from this channel, you are only allowed to read:

func log(cs <-chan string) { ...c := make(chan int) // buffer size = 0 c := make(chan int, 10) // buffer size = 10

c <- 1

x = <- c

Channels are typed values that allow goroutines to synchronize and exchange information.

func main() { timerChan := make(chan time.Time) go func() { time.Sleep(3 * time.Second) timerChan <- time.Now() // send time on timerChan }() fmt.Println("Started at", time.Now()) // Do something else; when ready, receive. // Receive will block until timerChan delivers. // Value sent is other goroutine's completion time. completedAt := <-timerChan fmt.Println("Completed at", completedAt) }

Let's use channels for communication:

func lecturer(c chan string) { for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { c <- fmt.Sprintf("%d Bla bla goroutines bla channels bla bla\n", i) time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond) } } func main() { c := make(chan string) go lecturer(c) for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { fmt.Printf(<-c) } }

We can also return an (outgoing) channel instead of passing it as parameter:

func lecturer() <-chan string { c := make(chan string) go func() { for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { c <- fmt.Sprintf("%d Bla bla goroutines bla channels bla bla\n", i) time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3)) * time.Millisecond) } }() return c } func main() { c := lecturer() for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { fmt.Printf(<-c) } }

The following code might look good at first sight, but causes a deadlock:

package main import "fmt" func main() { ch := make(chan int) ch <- 1 ch <- 2 // dead by now fmt.Println(<-ch) fmt.Println(<-ch) }

Expected output?

32Same code, but with a channel with buffer size 2 (instead of 0):

package main import "fmt" func main() { ch := make(chan int, 2) // channel with buffer size 2 ch <- 1 ch <- 2 // dead by now fmt.Println(<-ch) fmt.Println(<-ch) }

close(c)

value, ok := <-c

for {

x, ok := <-c

if !ok {

break

}

// do something with x

}

// channel closedWrite a generator for Fibonacci numbers, i.e. a function that returns a channel where the next Fibonacci number can be read.

func main() { fibChan := fib() // <- write func fib for n := 1; n <= 10; n++ { fmt.Printf("The %dth Fibonacci number is %d\n", n, <-fibChan) } }

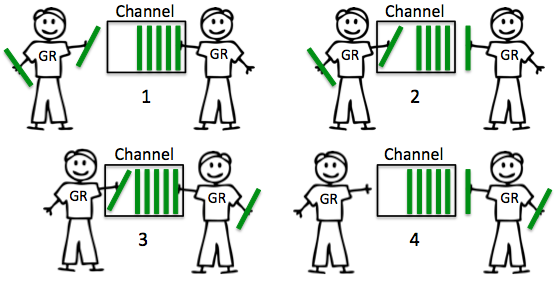

We're adding another (slower) lecturer to make it more interesting:

func lecturer(name string, speed int) <-chan string { c := make(chan string) go func() { for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d Bla bla goroutines bla channels bla bla\n", name, i) time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3*speed)) * time.Millisecond) } }() return c } func main() { a := lecturer("Anne", 1) b := lecturer("Bart", 2) for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { fmt.Printf(<-a) fmt.Printf(<-b) } }

// func lecturer(name string, speed int) <-chan string { ... } func fanIn(c1, c2 <-chan string) <-chan string { c := make(chan string) go func() { for { c <- <-c1 } }() go func() { for { c <- <-c2 } }() return c } func main() { a := lecturer("Anne", 1) b := lecturer("Bart", 2) c := fanIn(a, b) for i := 0; i < 10; i++ { fmt.Printf(<-c) } }

func lecturer(name string, speed int) <-chan string { c := make(chan string) go func() { for i := 0; i < 5; i++ { c <- fmt.Sprintf("%s: %d Bla bla goroutines bla channels bla bla\n", name, i) time.Sleep(time.Duration(rand.Intn(1e3*speed)) * time.Millisecond) } }() return c } func main() { a := lecturer("Anne", 1) b := lecturer("Bart", 2) for i := 0; i < 10; i++ { select { case msgFromAnne := <-a: fmt.Printf(msgFromAnne) case msgFromBart := <-b: fmt.Printf(msgFromBart) } } }

The select statement is like a switch, but the decision is based on ability to communicate rather than equal values.

select { case v := <-ch1: fmt.Println("channel 1 sends", v) case v := <-ch2: fmt.Println("channel 2 sends", v) default: // optional fmt.Println("neither channel was ready") }

Without default case, the select blocks until a message is received on one of the channels.

39

Write a function setTimeout() that times out an operation after a given amount of time. Hint: Have a look at the built-in time.After() function and make use of the select statement.

func main() { res, err := setTimeout( func() int { time.Sleep(2000 * time.Millisecond) return 1 }, 1*time.Second) if err != nil { fmt.Println(err.Error()) } else { fmt.Printf("operation returned %d", res) } }

Really.

More information about Go and concurrency:

41

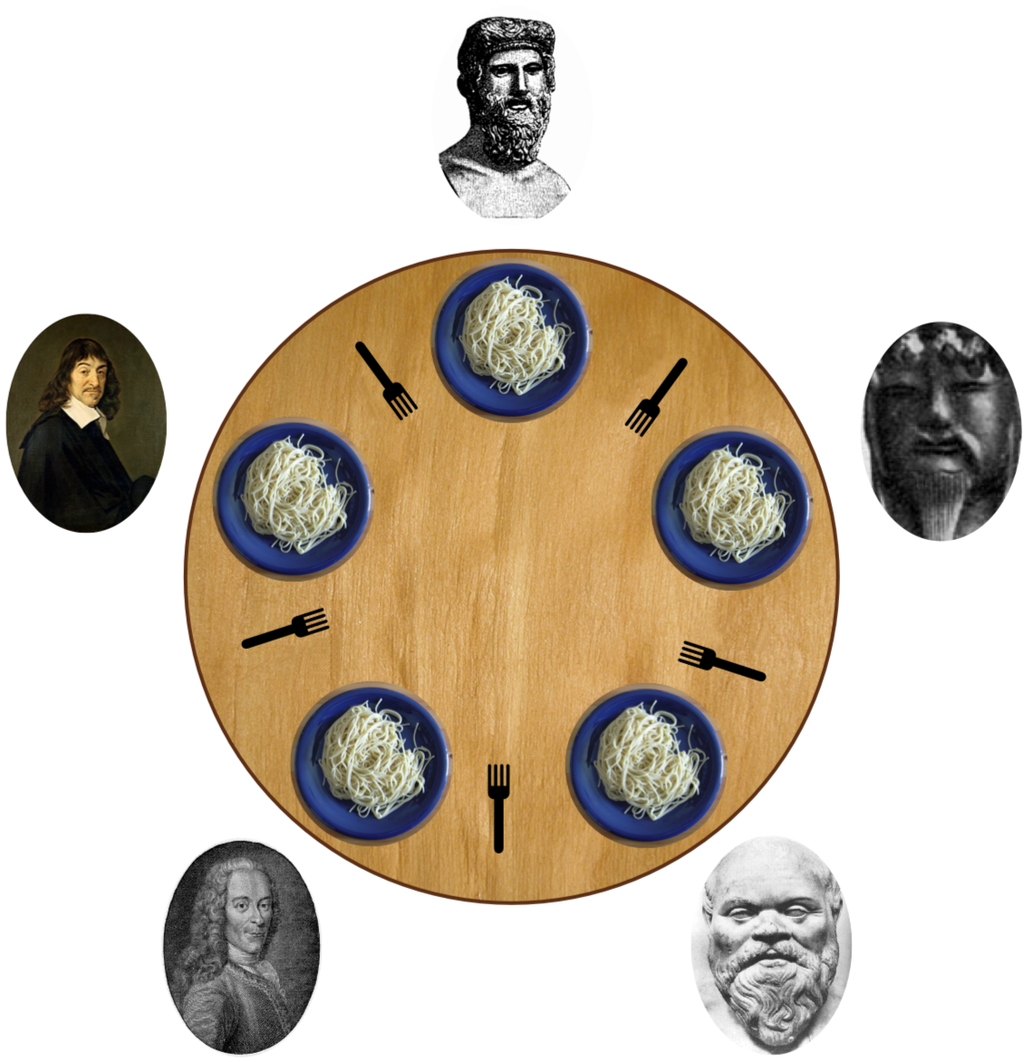

5 philosophers think either or eat. To eat the spaghetti each need 2 forks.

A hungry philosopher sits down, takes the right fork, then the left, eats, then puts the left fork on the table, then the right. Everyone uses only the one to the left or to the right of his place.

// Main loop

func (p *Philosopher) run() {

for {

p.takeForks()

p.eat()

p.putForks()

p.think()

}

}